V

The boy’s mother comes out of the cleaners carrying her sequined handbag and a pain between her shoulder blades. She steps off the curb and winces. The streets are always too crowded when I leave, she thinks, wishing they’d let her come in earlier as she whisks around the legless man perpetually posted at the corner with his misspelled sign propped in his lap. Strange, she thinks. Laps are something that we only make when we sit down, but this man has a lap forever. She wonders if he has kids who sit on his forever lap. Probably not, she relents. He looks too down-beaten to be around kids. He probably has some, but he would never see them, not in his condition. She thinks then of her son. She doesn’t want to, but she always does. Why can’t he be a good man like his uncle? Why does he have to be so much like his worthless father? She hates thinking about them on her way home, knows that if she starts she’ll spend the entire bus ride fretting over them and her, how they all fit together and fell apart. She hates spending these free moments on them, wanting instead to be inside herself thinking something nice while drifting off to the city lights and rhythms of the bus. It scares her that frequently their faces loom inside her private moments, as if the more they wrong her, the more of herself she gives away.

The bus takes a long time getting to the corner. She can see it down the line of buses because it’s the only green line that comes by here after noon. She wonders what lines passengers who take other green lines in the mornings take after getting out of work. They can’t just get on any bus, she asserts. They don’t go just anywhere. What if they lived out near the harbor? She doesn’t miss her car though she misses the freedom it represented. Sometimes on her lunch breaks she’d drive around the city, stopping at an unknown lunch cart or one of the Panero’s if she had some more money, just taking streets at random until she was certain she could just get herself back on time. That was years ago though, and with gas prices now she’d never spare the expense. I would if I still had it, she decides defiantly. If he hadn’t crashed it into a damn pole I would have it. Fitting that the boy would finish off what her husband tried. He’d just hawked it, stole the money out from her, and denied the whole thing. She’d had to go down to the garage and plead with the man to sell it back to her on a small profit. He’d already pieced some out from it, but she’d said she didn’t care. She couldn’t believe he could lie to her like that, saying that it’d been stolen. She knew he was lying though because she insisted they call the police and he’d turned defensive. She’d had to buy back her own damn car. The second time though, the boy left nothing for her to buy, only bills to pay from the town, the police, and the man whose car he’d hit before careening into the light pole.

She couldn’t help feeling the penumbra of their actions shadowing everything she was. She couldn’t force them out because they were always forcing themselves in. Like the rats, she thought, despicable crawling over her counters at night. They’ve taken over the neighborhood and no one will do anything about it. She laughs to herself imagining her son and husband as huge rats, but the image becomes mean and scary as their eyes glow red and they start tearing her flesh off, her mind-body flailing away from herself. She shivers in her light coat and presses herself against the building even though the bus is now upon her. Her arm shoots out instinctively pointing toward the street to flag the bus down. As she gets on and finds a seat, her mind miraculously clears and she settles in to watch the passing light flashes and street scenes as the bus rumbles away from the curb.

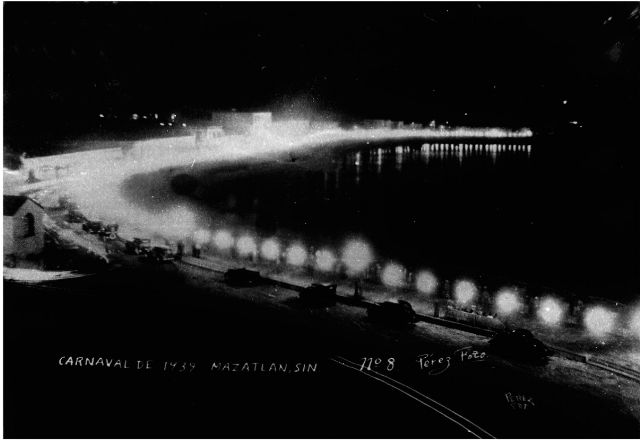

When she was a little girl the city was still young, and like her it hadn’t yet connected all of its lines, hadn’t gained the hard-edged geometry constricting the wayfarer’s possibilities into a terminating sum of possible routes. She remembered what it felt like to be that free, to move and be surprised at moving and the possibilities which a body could afford. Now she moved with the reserve of knowing not only the possibilities, but also the shortfalls and pains that block off some avenues, the rendered contortions that never really smoothed out. She felt the ache between her shoulders again and tried to straighten up in the hard plastic curve of the bus seat as a swath of neon penetrated through the smoke grimed windows, plastering her face purple and green in random explosions that faded to the tired grey of the dusk shadowed interior as they turned down a side-alley towards the outskirts of her neighborhood. She still had a while to go, though she considered a fairly large portion of the city to be her neighborhood, extending it beyond the norm to encompass a far-flung, hard-won network whose nodes corresponded to social bonds webbed together in a personal geography of proud women she could call on in a moment’s notice if only because a favor was owed her.

The light turned and she jumped inside herself, a little action she repeated at every light as if to cheer the driver on. Instead he hit the hydraulics, the chassis and cabin to bucking against the strain, and yanked open the doors to admit a stone faced, stout lady shawled and cowl necked against an imaginary chill who paid exact fair out of a cracked and ancient coin purse with a rosary wrapped hand before sidling down the isle with disdainful look for the passengers and settling her bags and bulk into a second row bench. The boy’s mother eyed her from behind, focusing on a point directly in the center of her head. Well, she imagined, I’ll never turn out like that. Wrapped in misery and loathing for life. She probably never loved anyone. She’d had friends like this woman in secondary school, she recalled, young girls whose eyes were set on limits beyond their means. They weren’t to take husbands or have normal lives. They’d never raise children or keep a nice home. Many of them became nuns, and while she loved the Virgin with all her heart she felt this to be a grave mistake. A woman should have a family. Even if it turned out rotten like hers, a woman should know that joy, if only for a little while.

The boy’s mother never got beyond this depth, casting the woman as a monster, in a matter of moments relegating all the ills of the world on her shoulders. Funny she never paused to consider herself amid all the accusations. The interior of the bus grew darker as night descended and they passed the park where only the few lone lamps lit the curved, tree-lined walkways. She never liked the park at night, especially from the bus where she relished the flash pans of neon and phosphorescent as they gilded the bus windows and slid along the faces of the passengers. She preferred to close her eyes against the glare and wallow in the projections cast on the inside of her eyelids. The park made her remember and for her the bus rides were a chance to forget, if only for one solitary moment of the day, the crushing weight and circumstance of her life.

A moth flocked porch light illuminates a drive of cracked pavement sandwiched between two doorways with matching with metal gating. A dead lily squashed with a rain drooped advertisement touches the edge of a frayed gauze weave welcome mat with a trodden plastic chrysanthemum at the upper left edge. The boy’s mother scuffs her shoe bottoms on the mat and slides the key home into the lock. She unlocks and locks the door three times, crosses herself, wipes her feet more, and crosses the threshold into the dark foyer. She hopes the boy is not there. Damn that boy, she thinks. Why should I hope my own son is not home this late? What kind of thought is that for a mother to have? Still, she has it.

She’s too tired to fix something to eat, but too hungry to go to sleep. She finds a half-eaten pastry from the bread man in the fridge where she keeps them safe from ants. It’s a few days old and stale, but the buttery dough is sweet and tastes good. She looks at the clock to see if it’s early enough for the bread man to come. He comes in the mornings and evenings but she is always off to work early and it’s too late now. She runs a glass of water and heads across the living room towards her bed. A shrine to the Virgin stands in an alcove in the wall, recessed at eye level. The boy’s mother stops before it, toeing at her leggings before composing herself. She begins to pray and her body calms.

She asks the Virgin to bring her peace. She asks that she keeps her job and for her mother and father to be looked after in heaven, that they know she thinks of them. She prays for the strength to carry on even with all her burdens, all the stilted architecture of her life so different than her girlhood imaginings. She’d never imagined it like this, she explains to the Virgin. With your love only, I move on. At the end, she prays for her son and her husband. She prays that the Virgin look over them and protect them even though they have strayed into evil. She looks at the Virgin before going to bed, and she knows the Virgin hears her. She knows the Virgin is by her side.

Tags: breadman, crime, everyday life, family, Mexico, ninis, urbanism, violence, youth, Zev Gottdiener