Pratfalls

I am asked to go to lunch with the visiting famous poet. I have watched many famous poets chew: Louise Gluck, Thomas Lux, Gerald Stern, Li Young Lee… If you have a couple books out and teach, you may be asked to lunch. No one will argue Mayakovski with you and slam your head into the tossed salad. The food is bland. The conversation is bland. The waiter looks like your Uncle Swen who committed suicide in 1972. You miss Uncle Swen. He made his own pickles. He never spoke above a whisper in a family where everyone else was Ralph Kramden. He taught you Chinese checkers. Poetry resides in remembering Uncle Swen. The poetry business resides in “I, too, dislike it.” Everyone dislikes the business. I don’t. It dislikes me. I would like to be good at it. I want to be shrewd and professional, and thin and tall – like Jim Daniels – and I want to schmooze, but I have no such gifts. I pay too much attention to the waiter because, right now, I feel he is my only link to sanity. I ask if I can have extra pickles. A vague smile makes his thin lips stretch. Yes. Uncle Swen…

I never called myself a poet. I believed someone else ought to accuse you of it. Many people ought to say, “you’re a poet!”, and then you back up against the wall, and a huge spotlight comes on and nails you there, and you say: “OK. OK. I’m a poet.” I wrote poems and worked the night shift in a mold-making plant in Kenilworth, New Jersey. I didn’t do this while getting my MFA. I did it for 21 years. I ground drills for a living. I also read Mayakovski, and May Swenson, and Ai, and the Iliad, and on and on, and scribbled in notebooks. Working in a factory means you get to practice on people who aren’t poets. There were bar readings then. I became so good at bar readings that I started getting features, and features led to being asked to do workshops. My factory job went belly up in 2002. I fell into poetry. It happened to me. I spent 20 years hosting readings outside the walls of academia. I am an outsider to academia, who has been allowed in as a sort of experiment. I don’t like professionals. They fired my friends. They outsourced my jobs. They made tool grinding an extinct skill. They talk of globalization, but are never made to suffer the worst aspects of it. Being a “professional” poet is like being traded to the team you hated as a kid. You need to make a living. You’re a pro. You need to give up the part of you who thinks: “there is something evil in this poetry business – something so evil it does not know itself as evil.” Slam as an alternative to the academy? Oh, I saw the same fake smiles and talk show kisses. People got drunk and fucked each other. But nowadays, the smart ones don’t get drunk. They don’t drink, they don’t fuck, they don’t curse. They’re like Satan – the eternal professional. What Satan didn’t like about God is that God was unprofessional. Satan is a purist. He never misses AWP and he knows exactly who, and who not, to talk to.

I am growing old and cranky. Why do I keep seeing the same interview with the same poet in Poets and Writers? Why does the first question out of a grad student’s mouth involve the names of publishers, contests, and who to contact? This is a business. I don’t forget. I am a worker – not a businessman. I like to produce poems and drill bits. Part of me is dying. I remember when I ground 200 drills one night, big drill bits, and, covered in grinding dust, I went out to the yellow trash bin, to the loading dock. There was a lilac bush out back – wild and unkempt – and I liked to close the door to the loud machines, and breathe it in. There was reprieve in that. I know people enjoy being professional. I don’t. I am forced to go upwardly mobile (that’s what they call it) as the ladder burns behind me, behind all of us. Where is my loading dock? The black cherry tree was still clinging to life out there. Lots of feral cats. The cold night air felt good against my dirty, oil-smeared face. Once, my pen slipped and kept on slipping. I don’t know anymore if the accident is sustainable – if the pratfall is convincing. I am teaching a course on the influence of vaudeville and parlor music on the first generation modernists. Last night I dreamed I was playing a grade B vaudeville circuit in Duluth. I had a compound fracture and the bone was jutting out from my dancer’s pants, but I kept doing tumbles and splits, and smiling, until some person yelled: “get that cripple off the stage.” I woke up and my baby daughter was lying against me, her head cradled in my arms. For a moment, I wanted to run away. There’s nowhere to run. Everywhere there is a workshop, and six award-winning poets to teach it.

I remember seeing Etheridge Knight read for a hundred bucks in a bar in New Brunswick, New Jersey. He was soft spoken, calm. He was two years from his death. I keep thinking about him, and Uncle Swen. Uncle Swen was going to show me how to make pickles from cucumbers. It never happened. He killed himself. Poetry never happened. It was all a slip of the pen. I forgive him and it. My baby daughter’s head smells so sweet. Kissing it in the dark, I think what might happen if I don’t get tenure. How’s that for a poem? Time to get up and watch the famous poets chew.

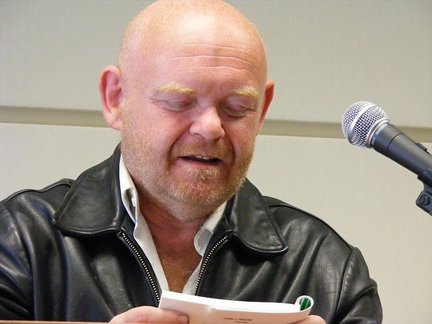

Joe Weil is an assistant professor at Binghamton University, or an associate professor. He forgets the distinction. He lives with his wife Emily and daughter Clare, and soon to be born (he hopes and prays), son Gabriel in Binghamton, New York, and teaches poetry at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. His books are on Amazon and his publications are in his curriculum vitae. He likes playing the piano and the guitar. People run when he plays the Irish tin whistle. This essay is from one of his improvisations.