by Carmen Mojica

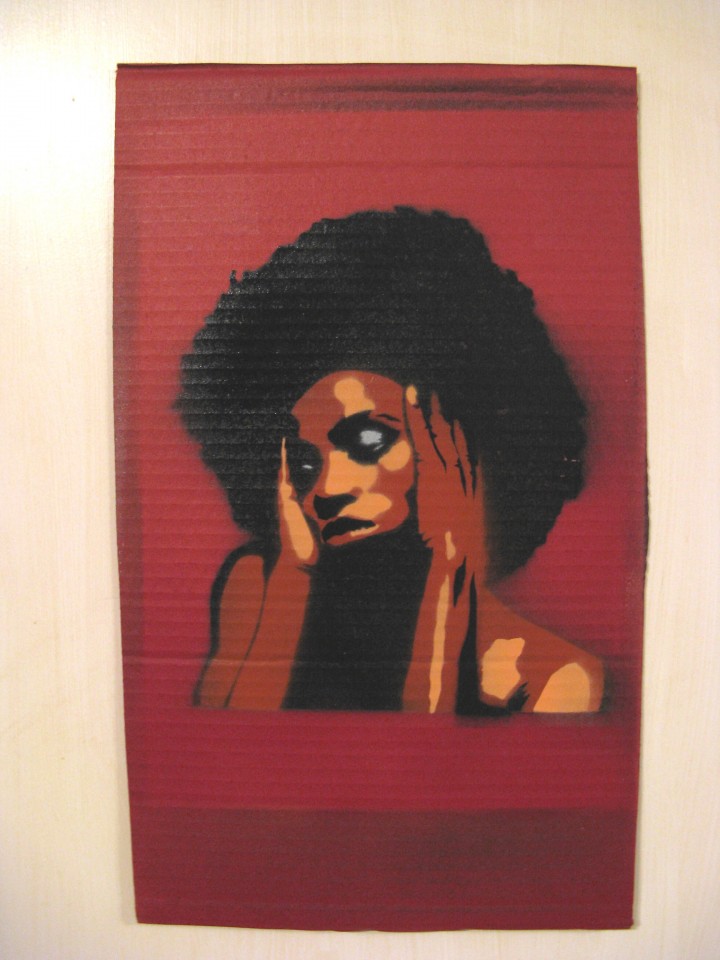

The first time I experienced an overzealous desire from some folks to rub my head was two years ago. I came back from a trip to Puerto Rico with a bald head, having taken clippers and a razor to my former Afro. I did not enjoy having my head touched without being asked. There are a lot of different emotions and thoughts that come with it. It seems peculiar to me – I consider my head an intimate space unto myself and anyone I allow to be so close. It hadn’t been the first time I cut my hair off. In December 2004, I freed myself of years spent chemically treating my hair. I had embarked on a journey in learning and reconnecting to my African roots. It was a mark of transformation and transition from complying with colonization to actively challenging and rejecting it, particularly colonization of the mind, body, and spirit.

Since I can remember, hair has been a concern in my life, most markedly when I got my first relaxer at age six. For thirteen years, I visited beauty salons at least once or twice a month to straighten my hair chemically. I was upholding the standard of beauty for womyn of color – a strict regimen of making sure the nappy hair was invisible. After ending that part of my life, I came across research on natural African hair that grounded me in the significance of head and hair beyond the history we are familiar with.

Before Africans were enslaved, African hair was worn natural and was very important in West African societies. The Wolof, Mende, Mandingo, Ibo and Yoruba people were the bulk of the enslaved people in the trans-Atlantic trade, which was focused in West Africa. In African cultures, the grooming and styling of hair have long been important social rituals. Elaborate hair designs, reflecting tribal affiliation, status, sex, age, occupation and the like, were common (White 49). The Afro in West Africa was a distinct, feminine trait. In the Mende nation, this type of hair was called “Kpotongo”, meaning “it is much abundant and plentiful.” The root word “Kpoto” means long and thick hair that grows like the forest, and reflects the Mende identification of women with the Great Mother Earth and the female principle of God (Ferrell 5). A person’s spirit was believed to be nestled in their hair.

I internalized this information as a source of pride in my natural beauty and a connection to my ancestors. This became deeper when I was studying the Yoruba tradition; the notion that the spirit was connected to the head further impressed on me. I learned that ori resided in a person’s head and so the importance of keeping the head spiritually, emotionally, and energetically cleared was deeply ingrained. In addition to the spiritual aspect of my head, there is of course a socio-political perspective to my stance.

People of the African Diaspora are often still perceived as less than human, being treated as objects and dispensable since the African Holocaust began. It goes then that a person of a darker hue’s body is somehow on display and public property, reminiscent of the years in which my ancestors spent being gawked and poked at on auction blocks, particularly in the Western Hemisphere. As a womyn of color, I have felt that the society around me acts as though my body is available to them whenever and however they’d like. This has also pushed me to be further protective of my head – in a world that has lost respect for personal space and the sanctity of a human’s body.

Works Cited

Ferrell, Pamela, and Carmen Lattimore. Where Beauty Touches Me: Natural Hair Care & Beauty Book. Washington, D.C: Cornrows & Co. Publications, 1993.

White, Graham, and Shane White. “Slave Hair & African American Culture In The Eighteenth & Nineteenth Centuries.” The Journal of Southern History 61 (1995): 45-76. JSTOR.

Tags: Carmen, Fabian, Hair, History, Mojica, Privacy, West Africa